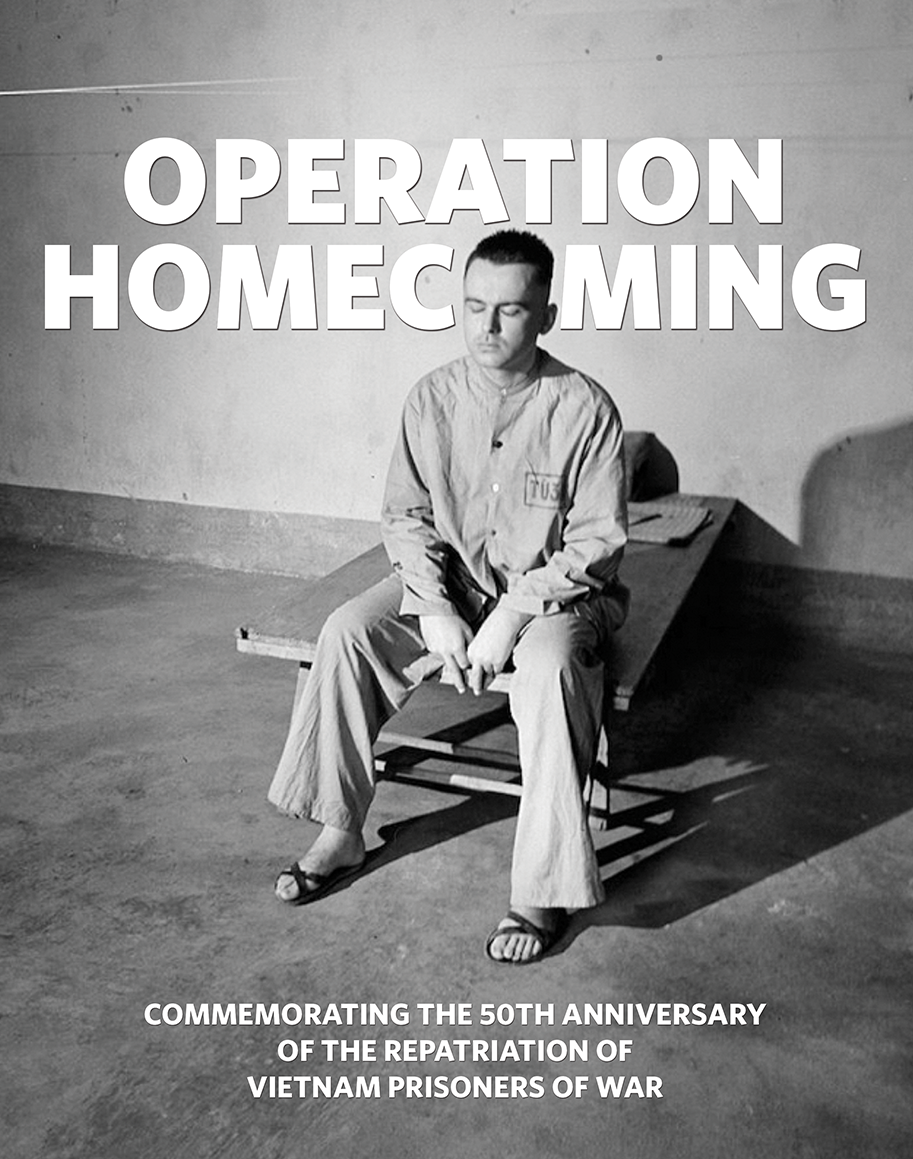

OPERATION HOMECOMING

COMMEMORATING THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE REPATRIATION OF VIETNAM PRISONERS OF WAR

Beginning in February 1973, 591 American prisoners of war (POW) were released and repatriated during Operation Homecoming. Among those were Naval Academy alumni who were Prisoners of War during the Vietnam War.

American POWs were often malnourished, put in solitary confinement and deprived of adequate medical care by their North Vietnamese captors. Torture was a regular occurrence.

Ten Naval Academy alumni shared with Shipmate how the Academy prepared them to endure and resist during their time as a POWs. They describe how critical the relationships forged with their fellow POWs were to surviving and what kept them going during the bleakest moments.

Their examples of leadership and patriotism provide a blueprint for future generations of officers and midshipmen. Here are their stories in their words.

Captain Peter V. Schoeffel ’54, USN (Ret.)

Then-Lieutenant Commander Schoeffel was flying an A-4C, a small attack aircraft originally designed for nuclear weapons delivery. He trained in his squadron (1958–62) to deliver nuclear weapons against the Soviets and their allies. On his final mission, on 6 October 1967, he led a flight of four A-4s in what was known as a “flak suppression mission.” The flak suppressors accompanied the aircraft whose mission it was to bomb and destroy a target and protect it by bombing any flak sites that might engage them. Captain Shoeffel spent more than five years as a POW until he was released on 14 March 1973.

“The wisdom of such a mission may be debated because it involves diving down what is essentially the gun crew’s line of sight,” Schoeffel said. “I would not be responding to these questions if I had not erred in my bomb switch setup, so I only released half my bombs. In order to complete my mission and not embarrass myself by bringing live ordnance back to the ship, I repeated my bomb run and ... was hit!” After ejecting from his plane and parachuting to the ground, he tried to hide in tall grass near the river that runs past Haiphong.

“Hiding was fruitless and I was soon discovered and taken prisoner,” he said. “Someone hit me with a gun butt, so I started bleeding a bit at my temple. Quickly, a noncommissioned officer or junior officer had a bandage put around my head. As I was marched past an antiaircraft artillery site, another soldier took the Navy watch off my wrist. I naively objected and was made to understand it would be returned later (hah!).”

Schoeffel was taken to a bomb crater near a village to hold him until higher-ranked officers arrived.

“During the two hours the villagers came to look, and an old woman tried her best to get at me,” he said. “She was making overhand clawing motions (like swimming) and leaning forward while being held back by soldiers. By this time, I had begun to respect the professionalism I thought I saw in the soldiers. Soon, I was picked up and after a one-hour trip was delivered to Hanoi and the Hoa Lo Prison, where my opinion was changed.”

Enduring and Resisting

My Naval Academy experience was strongly directed toward the concepts of responsibility and fulfillment of duty. Many hours of motivational films (during Plebe Summer) and tales of heroism in U.S. Navy, British Navy and U.S. Marine Corps traditions incorporated into the course in naval history inspired us midshipmen to hope to match in action the performances of historic naval heroes. Little at the Naval Academy related to, or prepared us for, resistance in captivity except for the underlying motivation not to fail in one’s service to the nation.

Relationship to our fellow POWs was specifically addressed in survival school and exposure/training related to the POW Code of Conduct. Being a prisoner and having a Navy or national responsibility as such probably did not enter my mind before my membership in an attack squadron engaged in flights over enemy territory.

Once I was captured, the relationships with my fellow POWs became of greatest importance. The continued existence of a chain of command and the recognition of a senior ranking officer having overall command gave purpose and meaning to behavior toward the captors. We surviving POWs cherish a brotherhood, trust and admiration for one another that is central to our life outlooks.

My bleakest times were after torture and in periods of expecting more. What kept me going was the knowledge of the justice of our nation’s cause in Vietnam and the confidence that the national leadership would eventually return us to the country and do so without sacrificing national honor.

Rear Admiral Robert H. Shumaker ’56, USN (Ret.)

Then-Lieutenant Commander Shumaker launched off Coral Sea on 11 February 1965 in an F-8 Crusader. He was a photo escort on an attack against a North Vietnamese military installation just north of the zone which separated the two countries. The low ceiling that day caused him to fly lower than planned, and as he fired his Zuni rockets and 20 mm machine guns, his plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire.

After ejecting, his parachute opened only 35 feet above the ground.He broke his back upon landing but managed to conceal himself in some nearby bushes. A short time later, a crowd of soldiers and civilians, all armed, marched past him shouting “Anglais” (French for Englishman) which gave him some hope he wouldn’t be detected.

One lagging soldier spotted Shumaker and aimed his AK-47 at him. After capture, he was handcuffed and paraded in front of a large audience in an auditorium where he revealed only his name, rank, serial number and date of birth as required by the Geneva Conventions. Later, he was put before a four-man firing squad.

“Happily for me they didn’t pull their triggers, but it certainly got my attention,” Shumaker said.

Then followed eight years of physical and mental abuse which ended when he was released on 12 February 1973.

“You can imagine how enjoyable it was to rejoin my wife and young son, continue my military career and appreciate even more the freedoms we have as Americans,” he said.

We Resisted

I had a tough plebe year, and that experience taught me the importance of staying physically fit and mentally alert, which let me stay one step ahead of the game. We used to joke about being injected with a “blue and gold” shot at “Canoe U.” But all joking aside, the Academy had instilled in me a sense of pride in being a naval officer with honor and integrity and leadership ability.

During my eight years as a POW, three were spent in solitary confinement alongside ten other guys who the Vietnamese considered leaders of the POW group. We were put into individual, windowless, concrete cells measuring only 4 feet by 9. Our ankles were bound together with metal clevises for most of the day. We named ourselves the “Alcatraz Eleven” and three of this group were U.S. Naval Academy graduates.

All three became flag officers after repatriation—Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale ’47, USN (Ret.), Rear Admiral Jeremiah Denton Jr. ’47, USN (Ret.), and myself. We communicated by clandestinely tapping on the wall, helping each other maintain our morale while enduring frequent torture sessions. Our captors tried to extract confessions from us and get us to cooperate with their propaganda efforts. We resisted.

Yes indeed, our Naval Academy background was an excellent training arena for learning how to survive such a situation. This awakening can help you too, although it is unlikely that any of you will become POWs in the future. However, each of you will certainly experience a setback as you experience the ups and downs of life.

Just remember that even good boxers occasionally get knocked down from time to time, and the secret to overcoming such a setback is to get back up off the canvas, dust yourself off, get back on your feet and get ready for the next round. We were a band of brothers simply trying to represent our nation with courage and resolve. We all wanted to be able to return to our homes holding our heads held high knowing that we had done our best in resisting the enemy’s efforts to exploit us. Our mantra was to “Return With Honor.”

Once I was in a small concrete cell with a drain hole at floor level. An adjacent cell was located about 5 feet away, separated by a cluttered hallway and it housed a Naval Academy graduate who had recently been shot down. He was badly injured and was depressed.

I had found and concealed a flimsy wire about 6 feet long. During the siesta hour I worked that wire into his cell (no small feat). After some hesitation, he reluctantly picked up his end of the wire fearing he would discover a “macho” guy on the other end who would make demands of him. The wire then suddenly disappeared only later to reappear with a toilet paper note attached explaining the “tap code” with the instruction to “memorize this code and then eat this note.” Today, that guy is a forceful motivational speaker who attributes that experience as having put him on a good path to resist and survive.

Throughout our imprisonment, used the tap code to support each other through the trials of solitary confinement.

The bleakest times I experienced were the days after a torture session when I felt that I had let my country and the Navy down. I still carry some guilty feelings. I had thought that I could resist and endure any torture they employed, but I soon learned that humans have physical limitations and that the reaction to extreme pain can be overwhelming. As time went on, we learned to give in just short of losing consciousness, so the statements that we were forced to make would be senseless and obfuscating.

One time they demanded to know what my job on the ship had been, so I told them I was in charge of all the pool tables on the carrier. They bought that ruse hook, line and sinker. Of course, you know that there are no pool tables on ships.

Captain Phillip N. Butler ’61, USN (Ret.)

Then-Lieutenant Commander Butler was flying an A-4C on 20 April 1965 over Vinh when malfunctioning bombs the aircraft was carrying exploded underneath him. He was forced to eject. Butler spent four days and nights trying to evade capture by the North Vietnamese.

Butler was released on 12 February 1973 and returned to the United States on 17 February 1973.

Give it Your All

Pride in being a naval officer and carrier pilot meant I didn’t want to give in to the Vietnamese interrogators and torturers. Also, I couldn’t let my fellow POWs, and even my family, down. We encouraged each other to give it your all, your best shot, resisting harassment and torture.

I learned teamwork at the Naval Academy.

Communicating and depending on my fellow POWs was critical to our survival. I doubt many would have survived the long years and come out whole without each other.

We lived by the motto “Return With Honor,” which means to return with your honor and like the guy you see in the mirror.

I created an ultimate list of 200 songs that I could play in my head. We taught and learned things for and from other POWs. We had classes even though we had no writing materials or books.

My cellmate for close to five years, Lieutenant Colonel Hayden Lockhart, is a 1961 graduate of the Air Force Academy. We were “classmates” so to speak. Hayden had a very dry sense of humor. One terrible day at the Briar Patch prison, where we were being tortured, Hayden said to me, “Don’t worry about these bastards, Phil. You and I have been harassed by professionals.”

He was referring to our plebe years. Very funny of course but also not true. No preparation for torture. But, I would say it was the ultimate test of a man.

“On the strength of one link in the cable,

Dependeth the might of the chain.

Who knows when thou may’st be tested?

So live that thou bearest the strain!”

I thought of this poem I was required to memorize as a Plebe thousands of times.

Commander Paul E. Galanti ’62, USN (Ret.)

Galanti was shot down on his 97th combat mission while flying an A-4C Skyhawk over North Vietnam on 17 June 1966. He spent seven years at the Hanoi Hilton as a Prisoner of War. During a 1967 propaganda photo shoot, Galanti defiantly flashed both middle fingers downward as he sat on a cot.

He said he tried to remain optimistic during his time as a POW. He said he appreciates the sacrifice of the more than 58,000 Americans who gave their lives during the Vietnam War.

“Every time I think about how bad I had it, I think about CommanderEverett Alvarez Jr. who got shot down 22 months before I did, and I don’t feel so bad. No matter how bad you have it, someone else has it worse. You just press on.

When I speak to the midshipmen, I just tell them it’s a piece of cake.

I consider it Plebe Year Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot, Golf and Hotel. Anybody could do it. Naval Academy alumni were the true leaders in the POW camp, starting with Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale ’47, USN (Ret.), Rear Admiral Jeremiah Denton ’47, USN (Ret.), and Vice Admiral William P. Lawrence ’51, USN (Ret.).

I realized how much the Naval Academy meant to helping us get through.

The two things I learned from those guys at Hanoi was I wasn’t as tough as I thought I was and no matter how bad I thought I had it, somebody else had it worse. There’s no such thing as a bad day when there’s a doorknob on the inside of the door.”

Captain David W. Hoffman ’62, USN (Ret.)

On 30 December 1971, then-Lieutenant Commander Hoffman was attached to Air Wing 15 staff as a landing signal officer, and he launched in a VF-111 “Sundowners” F-4 from Coral Sea. He was the wingman providing fighter protection for a major air wing strike against the highly strategic and heavily defended Vinh Transshipment and Storage Area in North Vietnam.

Early into the mission, they were taking heavy surface-to-air missile fire. He pressed on to the target, attracting missile fire away from the strike group, which went on to successfully attack the target and return without loss or damage. His plane was struck by the last of five missiles fired at them. Hoffman and his naval flight officer ejected at about 25,000 feet and at very high speed. The wind flail caused his arm to hit the canopy rail on the way out of the cockpit, breaking it near the shoulder.

He was shot in the foot while still in the air. Local villagers held them until the arrival of North Vietnamese soldiers, and they were transported directly to the Hanoi Hilton. Hoffman was kept in solitary confinement for the next 90 days and received minimal care for his injuries. His broken arm was used for leverage several times during his time as a prisoner.

Hoffman was repatriated on 28 March 1973.

Critical Relationships

When I am asked how my time at the Naval Academy prepared me for to endure torture and captivity, I typically reply, “Nothing prepares you for this.” But you have some sense of knowing you can gut things out if you take it a day at a time, sometimes an hour or a minute at a time.

The relentless pressures of Plebe Summer and the following years, the discomfort, the discipline, the sense of accomplishment when you do something right, helped get me through. Above all the bonds with classmates, company mates, teammates and knowing you are stronger together—that is what got me through my time as a POW, finding that same strength and support with my fellow POWs.

When I was weak, others held me up, perhaps not physically, but mentally and spiritually. When I was strong, I did the same for others. Those relationships were critical, because they allowed me to hope, and to believe, I would go home, to family, to friends, to normal life. At the Naval Academy, I learned to compartmentalize and focus on what I could control in the near term. I used that skill with regularity during interrogations and punishments, as well as just getting through every day. We came together as a group under some fine leaders who suffered the same or worse than we did.

People are always amazed at the humor we managed to find, another thing that bonded us. We were humans held in horrible conditions and treated, not as prisoners of war, but as criminals. If you’ve never looked at Mike McGrath’s illustrations, I recommend it, as those tell the story of what happened to us on a daily basis. We pulled off some things, well-documented in various books, to show our defiance and resistance, some of which were pretty darned funny to us.

As I reflect on my Naval Academy experience from my Plebe Summer in 1958 to June Week in 1962, as time has passed, I can tell you it wasn’t the book learning about naval warfare, strategy, history and case studies that were critical to my mental and physical survival. It was the knowledge I gained that I could absorb pain, discomfort, punishment, sleep deprivation, mental despair and other trials and somehow dig deep and get through it. Doing this in company with others suffering the same things, just like at the Academy, were critical on the really bad days and nights, when messages of comfort would be conveyed through the tap code.

In response to those who wonder what kept me going during the worst times, it was my belief in God, thoughts of home and family and strong help from fellow prisoners.

I am glad we were asked to share our stories and insights. It is important that the Naval Academy never loses sight of what going in harm’s way actually means on a personal level. The best thing they can do for midshipmen is to hold them to high standards, make them accountable for their choices and challenge them with a rigorous approach to professional development.

The Naval Academy is most definitely “N*ot” College,” to quote our sponsor midshipman family, nor should it be. It should be painfully hard, high pressure and demanding, testing mental stamina, the will to endure and core confidence in a safe setting. That is a gift I hope they never have to use in the conditions under which I was held and treated.

They will learn to trust themselves to handle unbelievably hard situations, and most importantly, develop those bonds that allow them to survive the greatest of challenges in their lives. I lived to come home, return to my family, my career and active flying with four operational commands (VF-41, Air Wing 8, New Orleans and Kitty Hawk), definitely banged up but bearable.

I am quite certain my Naval Academy experience was a foundational element in my ability to do that, along with pure stubbornness that I would not let them win.

Captain John “Mike” McGrath ’62, USN (Ret.)

Then-Lieutenant Commander McGrath was flying his 179th mission over enemy territory in an A-4C Skyhawk when he was shot down by antiaircraft artillery on 30 June 1967 south of Hanoi. During ejection, he suffered a broken and dislocated arm, fractured vertebrae and a dislocated knee.

A shoulder and elbow were dislocated by his North Vietnamese captors during torture sessions. Like many of his fellow POWs, he was denied medical care. He was released on 4 March 1973 and returned to the United States on 7 March 1973.

McGrath published a book of his drawings, Prisoner of War: Six Years in Hanoi, that graphically detail the conditions POWs lived in and the torture methods they were forced to endure.

“I compare my time at Hanoi to plebe year. When they dislocated my elbow, I told myself, ‘if I can survive plebe year, I can survive this.’ I was in pain and was pushed beyond my breaking point. The discipline during my plebe year to get through an impossible situation—I wasn’t going to let the first class beat me at the Academy.

I applied that to my enemy. It was a difficult time. You get demoralized with no rescue in sight. You think you’re going to die there. That Naval Academy training was really helpful to me. The lesson of being true to your people and mission and my fellow prisoners. We were true to our classmates and to our fellow prisoners.

Unbreakable Bonds

Relationships with my fellow Prisoners of War were all-important. You could trust them and they could trust you. You built loyalty. You built friendships that last to this day. You formed a bond that could never be broken.

We told each other to give the guards false answers. If they torture you again, make them break you again. Everybody broke. They just didn’t take no for an answer. No one was tough enough to stick to name, rank and serial number.

You have to control your emotions. You have to have patience. Solitary is the worst torture of all. Your mind is racing all day long. With no input, your mind continues to race and you have to fill your mind with something.

I started memorizing things I learned tapping through the wall with my fellow prisoners. They started filling my mind with names. I memorized 355 POW names. I had a roommate who spoke German and Phil Butler was fluent in Spanish. I learned 8,000 Spanish words without ever picking up a book. You memorize everything you can and memorize every detail of information you can squeeze out of your source.

You keep your mind working and working. It gets you through months and years by extracting information from your fellow prisoners.

Captain David J. Carey ’64, USN (Ret.)

Then-Lieutenant Commander Carey was on an Alpha strike on a small railroad bridge inland from the port city of Haiphong on 31 August 1967 when a surface-to-air missile blew the tail off his A-4. Spinning upside down, he ejected passing 4,000 feet, landed in a small North Vietnamese village and was immediately captured. He was taken to Haiphong and then Hanoi.

He was released on 14 March 1973.

Be a Man of Honor

The rigors of life at the Naval Academy, the pace, the daily demands, the emphasis on honor, striving to do our best, the pressure of trying to balance everything, somehow all this and more, I saw as excellent preparation for enduring and resisting over time. (Not to mention plebe year’s contribution—and I might point out that ’64 was the last class to have a plebe year.)

I’d be remiss not to mention former Naval Academy wrestling Coach Ed Peery’s influence on my life. He had absolute conviction that I was tougher both physically and mentally than I ever realized or believed.

My honor was sacred and even though I might often fall short, I was to always strive to be a man of honor and do the best that I could do.

Life Blood

Our relationships were our life blood. We all had good days and bad days. On the good days I carried and encouraged others. On the bad days others carried and encouraged me.

Beyond that, my POW experience was exactly like the adage about flying, “Flying is hours and hours of sheer boredom interspersed with moments of stark terror.”

During the “hours of boredom” my fellow POWs were entertainment, education, encouragement, safety and brotherhood. During the hours of “stark terror” they were strength, encouragement. I knew that no matter what, they would forgive me, recharge my strength— both physically and mentally—and accept me just as I was.

When I was tortured to the point of having no control over my mind, long past the time when I could move my arms or get off the floor, the faithfulness of God in the form of a Psalm that I had learned as a child came to mind and provided an anchor. “The Lord is my shepherd …”

That was no accident.

Scripture tells us over and over again that God is faithful. Not me. Not you. We all have faith … in something … the question really is, “Is that in which we place our faith, worthy?”

Captain Read B. Mecleary ’64, USNR (Ret.)

Mecleary was flying an A-4E on a flak suppression mission on 26 May 1967. The target was Kep Airfield. His aircraft was hit by antiaircraft artillery. He left the formation and attempted to head for the coast. Shortly after leaving the formation, his aircraft received additional damage from a surface-to-air missile.

Mecleary ejected, parachuted to the ground and upon landing, he realized his legs were badly injured. He could not stand or walk. He radioed he was alive, but injured, then destroyed his survival radio to ensure the enemy would not be able to use it to lure other U.S. aircraft into a trap thinking the radio signal was from a downed pilot. He was captured about 30 minutes later.

Duty and Honor

I’m not sure anything can really prepare someone for the experience of being a POW. Certainly, our Survival School experience was pretty far from the reality we experienced. But, our years at the Naval Academy did instill a very strong sense of duty and honor.

It introduced us to the Code of Conduct which gave us a base from which to start with our resistance and endurance. The Academy also helped us build our confidence that we could pretty much get through or accomplish anything we set our minds to.

Our fellow POWs were the true backbone of our ability to survive, endure and resist. They were supportive of us throughout and provided understanding, kindness and guidance in so many ways. They were always there for us—always. In my case, most were senior to me and provided a wealth of knowledge on so many aspects of the military and life in general.

Our senior leaders were absolutely superb. Taking the brunt of the torture in many instances, their leadership never faltered. In my personal case, I was very badly injured during my ejection and was unable to walk for approximately four months. My first cellmate was an Air Force major, ten years my senior. I credit him with helping me to stand and walk again over those difficult months. He saved my life!

Captain Joseph “Charlie” Plumb ’64, USN (Ret.)

Then-Lieutenant Junior Grade Plumb was flying the F-4 Phantom off the aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk on 19 May 1967. His plane was hit by a surface-to-air missile and he and his radio intercept officer ejected just south of Hanoi. They were captured immediately, tortured and spent the next 2,103 days in Communist prison camps.

‘Elected to be Victorious’

The “Supe” in the early 60s was Rear Admiral Charles Kirkpatrick ’31, USN (Ret.). We called him, “Uncle Charlie.” His mantra was, “You can do anything you set your mind to do!”

Before every football game, we would see the veins pop in his brow as he would clinch his fists and say, “And you guys can do it!” Those were the days of Roger Staubach ’65 and Captain Joe Bellino ’61, USNR (Ret.), and great Navy teams!

Kirkpatrick told us that it wasn’t the challenges around us that shaped our destiny. It was the choices we made about the challenges around us that would. In the prison camps, I found that to be true. We could choose to be victims or victors. We elected to be victorious.

Relationships were vital … lifesaving. I wouldn’t have survived (and even thrived) without the strong support group of my fellow POWs, many Naval Academy grads. After a very painful torture session, I would be thrown back into my cell with a feeling of guilt that I hadn’t been stronger.

After the guards had cleared the area, the guys next door would tap out the familiar, “Shave-and-a-haircut” call up. I would crawl across the dirt floor, press my ear to the wall and listen for the “tap code.” “You’re going to be okay,” the taps would say, “We’re with you. GBU (God Bless You) Plumber.”

My faith kept me alive. Faith in God, faith in my country and faith in my fellow warriors.

Captain Theodore W. Triebel ’64, USN (Ret.)

Then-Lieutenant Commander Triebel was flying a F-4B Phantom, attached to Fighter Squadron 151, on board Midway. He was on his fourth combat deployment, and his 327th mission on 27 August 1972 providing armed escort for an unarmed RF-8 Crusader. The photo plane was to take battle damage assessment pictures of two bridges on a road segment south of Hanoi.

After the photos were taken and they turned around, several surface-to-air missile sites had become active. Seven or eight missiles were launched at them. While maneuvering to evade, one missile exploded behind Triebel’s plane causing major damage.

Ejection seats and parachutes worked as advertised, though wind impact at ejection caused flaying. Floating down, he made a call on his survival radio letting “everyone” know they were shot down and had two good chutes. He landed hard on the side of a karst, an area made of limestone. A village was below and local militiamen were shooting. Triebel heard the bullets ricocheting off the rock formations close to him. In less than a few minutes later, he was surrounded by rifle-toting soldiers and captured.

Others Before Self

My four years at the Naval Academy brought forth, and solidified, the personal and professional value of strong friendships when dealing with adversity. As midshipmen, we were faced with achieving common goals as a team. That could be as plebes supporting each other under stress, as company mates in various competitions or in group academic tutoring sessions and varsity sports.

My time on the heavyweight crew team was particularly notable for developing insights on the importance of cohesiveness to achieve success. Indeed, as middies we learned such camaraderie meant putting others before self. These functionable attributes were planted and grew under the overarching Naval Academy mission: to develop midshipmen morally, mentally and physically.

I’m pleased to note that’s the exact same Academy mission as today. It works.

As a POW, stressors were many. There was nothing more important than having a fellow POW to lean on, to share with, to rely on, to console with and to fight with in an extremely hostile environment.

Sustained by Faith

The evening after being shot down, I was taken to a nearby village. There was a gauntlet of villagers lined up with various farm implements in their hands. They were angry, yelling and ready to have me enter.

I was tied and a blindfold was taken off, as militiamen jabbed with rifles indicating I had to go through this awaiting throng. What came to my mind entering the gauntlet was what I’d learned in Sunday school, part of the 23rd Psalm. “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me, thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.”

___________________________

COURAGEOUSLY DEFIANT

NAVAL ACADEMY ALUMNI HELD AS POWS DEMONSTRATED ALLEGIANCE TO EACH OTHER AND THEIR COUNTRY

The following stories of deceased Naval Academy alumni who were POWs in Vietnam are far from complete. Their journeys of service, sacrifice and persistence have filled volumes of books. It is Shipmate’s intent to recognize the heroes who survived unimaginable physical and mental abuse to return home with honor. They exemplify the values the Naval Academy instills in midshipmen.

RADM Jeremiah Denton Jr. ’47, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 18 July 1965

Released: 12 February 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1230, arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1625.

Denton was shot down while leading an attack over a North Vietnam military installationon 18 July 1965. In defiance of his captors, Denton blinked the word “torture” in Morse code during a 2 May 1966 interview by a Japanese television reporter. It was the first evidence relayed to the American military intelligence community that U.S. POWs were being tortured.

Rear Admiral Denton was imprisoned in the Hanoi Hilton where he spent four years in solitary confinement. As a senior officer among the POWs, Denton set policies for handling interrogations and communicating without raising the suspicions of their captors.

“As a senior ranking officer in prison, Admiral Denton’s leadership inspired us to persevere, and to resist our captors, in ways we never would have on our own,” said fellow POW Captain John S. McCain ’58, USN (Ret.). Denton earned the Navy Cross, the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, three Silver Stars and the Distinguished Flying Cross.

VADM James B. Stockdale ’47, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 9 September 1965

Released: 12 February 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1405 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1655.

Stockdale broke a bone in his back while ejecting from his plane on 9 September 1965. He was attacked by local townspeople on the ground. He suffered a broken leg and a paralyzed arm.

He was the highest-ranking Navy officer POW in Vietnam. He refused to cooperate with his captors and devised ways for POWs to communicate. Stockdale established rules for prisoner

behavior—BACK U.S. (Unity over Self). He set the example for resistance by taking extreme measures to deny attempts to use him as a propaganda tool.

In 1969, he beat himself in the face with a wooden stool when told he would be paraded in front of journalists. Stockdale knew his captors would not allow him to meet reporters with a

disfigured face.

While his actions inspired his fellow POWs, Stockdale was frequently tortured. He spent two years in heavy leg irons and four years in isolation. When he learned some prisoners died during torture, he slashed his wrists to demonstrate to his captors that he preferred death to submission.

Stockdale delivered vital information to the American intelligence community through coded letters with his wife, Sybil. Sybil Stockdale also played a critical role—along with the wives

of other POWs—in keeping POWs and those missing in action in the nation’s consciousness. She founded the National League of Families for American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia.

He was the most decorated naval officer of the Vietnam War. Among his awards were the Medal of Honor, Distinguished Flying Cross and Bronze Stars with Combat “V.” Stockdale was selected as a Distinguished Graduate Award recipient in 2001.

CAPT Homer L. Smith ’49, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 20 May 1967

Smith was tortured to death by his North Vietnamese captors on 21 May 1967. His remains were returned to the United States on 13 March 1974. On 29 May 1974, memorial services were held at the Naval Academy Chapel and interment was in the Academy cemetery with full military honors.

On 20 May 1967, Smith was shot down by ground fire while leading a strike group in an A-4 Skyhawk over North Vietnam. He was observed successfully ejecting and was captured upon reaching the ground. He was on his second combat tour in Vietnam, having completed more than 129 combat missions during his first tour.

Smith was awarded the Navy Cross, Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross (two awards), the Legion of Merit with Combat “V,” Purple Heart, Bronze Star, Navy Commendation Medal (three awards), Presidential Unit Citation, Vietnam Campaign Medal, Vietnamese Meritorious Unit Citation and Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry.

CAPT Allen C. Brady ’51, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 19 January 1967

Released: 4 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1425 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1730.

Brady was executive officer of Attack Squadron 85, flying off Kitty Hawk and leading a flight of A-6s against a bridge complex in North Vietnam when he was shot down on 19 January 1967.

He was captured by the North Vietnamese and was subject to “extreme mental and physical cruelties in an attempt to obtain military information and false confessions for propaganda purposes,” his Silver Star citation reads. “Through his resistance to those brutalities, he contributed significantly toward the eventual abandonment of harsh treatment by the North Vietnamese, which was attracting international attention. By his determination, courage, resourcefulness and devotion to duty, he reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the Naval Service and the United States Armed Forces.”

After returning home, Brady’s assignments included serving as commander of Medium Attack Wing ONE at NAS Oceana (August 1974–June 1976), and on the staff of the Chief of Naval Education and Training at NAS Pensacola (July 1976 until his retirement from the Navy on 1 October 1979).

RADM Robert B. Fuller ’51, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 14 July 1967

Released: 4 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1500 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1811.

Fuller was a Skyhawk pilot and the commanding officer of Attack Squadron 76 onboard Bon Homme Richard. On 14 July 1967, he launched in his A-4C on a mission near the city of Hung Yen in Hai Hung Province, North Vietnam. During the mission, his 110th, as he was just northwest of the city, Fuller’s aircraft was shot down.

He ejected from the aircraft and was captured.

During captivity he was tortured by ropes, leg irons and spent 25 months in solitary confinement. Fuller spent 68 months in captivity. He was awarded the Navy Cross, two Silver Stars, four Distinguished Flying Crosses, two Bronze Stars, two Purple Hearts and the POW Medal.

He was one of the naval aviators who flew the flight sequences for the movie The Bridges at Toko-Ri in 1954.

CAPT Charles R. Gillespie ’51, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 24 October 1967

Released: 14 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1430 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1715.

Gillespie served in numerous flying assignments before flying combat missions in Southeast Asia with Fighter Squadron 151 off aircraft carrier Constellation from June to November 1966 and then off aircraft carrier Coral Sea from August 1967 until he was forced to eject over North Vietnam and was taken as a prisoner of war on 24 October 1967. He spent 1,969 days in captivity.

After coming home, he served as a test pilot, chief of staff for plans and programs of the Naval Air Test Center, commanding officer of NAS Patuxent River, MD, and as deputy commander of the Naval Air Test Center at Pax River, from June 1975 through October 1982.

VADM William P. Lawrence ’51, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 28 June 1967

Released: 4 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1500 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1811.

Lawrence was the commanding officer of Fighter Squadron 143 onboard Constellation. On 28 June 1967, Lawrence was flying a mission over Nam Dinh, North Vietnam, in a F-4B Phantom when his aircraft was hit by enemy fire.

Lawrence was subjected to five consecutive days of torture by his captors. For the next six years, Lawrence was held prisoner in the Hanoi prison system. He memorized the rank and name of every POW and shared the “tap code” POWs used to secretly communicate with each other.

“He repeatedly paid the price of being perceived by the enemy as a source of their troubles through his ‘high crime’ of leadership,” his fellow POW Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale ’47, USN (Ret.), later said, “[but he] could not be intimidated and never gave up the ship.”

During an extended period, isolated in a small cell, Lawrence wrote a poem about his home state, “Oh Tennessee, My Tennessee,” which is now the official state poem. Lawrence served as superintendent of the Naval Academy from August 1978 to August 1981. Lawrence was selected as a Distinguished Graduate Award recipient in 2000.

CAPT James P. Mehl ’51, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 30 May 1967

Released: 4 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1500 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1811.

Mehl was an A-4E pilot assigned to Attack Squadron 93 onboard Hancock.

On 30 May 1967, Mehl was the section leader of a two-aircraft strike group assigned targets in Thai Binh Province, North Vietnam. Upon entering the target area, Mehl and his wingman began receiving indication that a surface-to-air missile site to the north was preparing to launch a missile. Mehl eluded one missile and maneuvered his aircraft to fire his strike missiles at the site. When in a 10 degree nose-high altitude, a second missile impacted the underside of his aircraft. Mehl turned toward the water, but was forced to eject near the city of Hung Yen and was captured. Mehl’s honors and decorations include the Silver Star, Legion of Merit with “V” device, the Distinguished Flying Cross, two Bronze Stars and two Purple Hearts.

CAPT Wendell B. Rivers ’52, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 10 September 1965

Released: 12 February 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1405 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1655.

Rivers was a member of Air Wing 15, Attack Squadron 155 flying A-4 Skyhawks from aircraft carrier Coral Sea. On his 96th mission, 10 September 1965, he was shot down and captured at Vinh, North Vietnam. He spent 2,712 days in captivity. Rivers earned the Silver Star, Legion of Merit with Combat “V” and Distinguished Flying Cross.

After recovering from injuries suffered in Vietnam, he was assigned to Naval Air Systems Command in Washington, DC, until his retirement from the Navy on 31 December 1976. Rivers also served aboard the destroyer Agerholm during the Korean War. He entered flight school in 1953.

Col George R. Hall ’53, USAF (Ret.)

Captured: 27 September 1965

Released: 12 February 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1405 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1655.

Hall began flying combat missions over Vietnam with the 15th Tactical Fighter Squadron in May 1963. On 27 September 1965, he was flying photo reconnaissance near Hanoi when his RF-101 Voodoo was hit by ground fire. He ejected and was captured.

During his time as a POW, Hall would harken back to his days on the Naval Academy golf team and visualize playing on familiar courses, using a stick in his 7-foot by 7-foot cell, according to a 3 June 2014 post on the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and Museum website. This exercise helped Hall keep his sanity through the horrendous conditions he and his fellow POWs endured.

After returning to the United States, Hall served as an aide to Colonel John Flynn at Keesler Air Force Base, MS, and then attended Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base, AL. He served as deputy commander of operations for the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing at Bergstrom AFB, TX, flying the RF-4C Phantom II. Hall retired from the Air Force on 31 July 1976.

CAPT James F. Bell ’54, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 16 October 1965

Released: 12 February 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1405 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1655.

Bell was flying a reconnaissance mission north of Haiphong when he was shot down on 16 October 1965. He was able to reach the sea, but he and his crewman were picked up by a local fisherman 30 minutes later. Bell was tied to the boat’s mast and then beaten by a “crowd of angry North Vietnamese en route to the first of several prisons,” according to Captain Bell’s obituary in the Washington Post.

He spent two months in leg chains for refusing to answer an enemy questionnaire. After his return to the United States, Bell served with Fleet Composite Squadron Seven from August 1974 to November 1975, and then with Naval Air Headquarters at the Pentagon from November 1975 until his retirement from the Navy on 1 March 1979.

Bell earned two Silver Stars, two Legions of Merit, the Bronze Star with Combat “V” and the Purple Heart.

VADM Edward H. Martin ’54, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 9 July 1967

Released: 4 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1500 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1811.

Martin’s A-4 Skyhawk was hit by surface-to-air missiles on 9 July 1967 while leading a bombing mission off Intrepid southeast of Hanoi. He ejected and was captured.

His Vietnamese captors broke his shoulders through rope torture. He spent his first year of captivity in solitary confinement. He was confined in leg and wrist irons and was beaten regularly. Eventually, Martin was placed in a 78-inch by 60-inch cell with four other men who were forced to sleep on concrete.

Following his return to the United States, Martin served as deputy chief of Naval Operations for Air Warfare (June 1974–August 1975); commanding officer of aircraft carrier Saratoga; chief of current operations for the commander-in-chief of U.S. Pacific Command (July 1979–November 1980); chief of Naval Air Training, where he served until January 1982; and commander of the United States Sixth Fleet. His final assignment was as United States commander, Eastern Atlantic, and the deputy commander- in-chief of U.S. Naval Forces Europe, where he served from January 1987 until his retirement from the Navy on 25 June 1989.

CAPT Ernest A. Stamm ’54, USN

Captured: 25 November 1968

Stamm was conducting a photo recon flight along the 19th parallel in North Vietnam on 25 November 1968 off Constellation. His aircraft was flying at about 5,500 feet and 550 knots when it was targeted by an antiaircraft artillery site.

The pilot maneuvered his aircraft to break the gunners’ aim, but his F-4 escorts saw the Vigilante explode in flight. Although two parachutes were sighted, there was no contact with the crew.

Stamm was captured and reported to have died on 16 January 1969 of injuries received during the shoot-down. His remains were repatriated on 13 March 1974 and positively identified on 17 April 1974.

After attending Nuclear Weapons Training, he served as special weapons officer on the staff of the commander, Carrier Air Group FIVE (December 1960–July 1962), followed by service as an instructor with the Navy ROTC detachment at the University of South Carolina (August 1962–August 1965). Stamm served as an RA-5C pilot with RVAH-5 from November 1967 until he was forced to eject over North Vietnam. His awards include the Distinguished Flying Cross and Prisoner of War Medal.

CAPT Edwin A. “Ned” Shuman ’54, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 17 March 1968

Released: 14 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1515 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1811.

Shuman was shot down north of Hanoi on St. Patrick’s Day 1968. He broke his right arm and shoulder when ejecting from his A-6 Intruder. He spent about 17 months in the Hanoi Hilton prison in solitary confinement.

Around Christmas 1970, North Vietnamese prison guards rejected Shuman’s request for the POWs to hold a church service. Despite knowing the consequences, Shuman led the 42 other POWs in a prayer session. Guards forcibly took Shuman away and the next four ranking officers stepped up one at a time before being escorted to a session of physical abuse.

Recognizing a united front, the guards allowed the POWs to hold weekly church service from then on, until their release in 1973.

“It was the first confrontation of the camp’s regulation,” Everett Alvarez Jr., the first Navy pilot to be shot down and held as a North Vietnam POW, told the Washington Post. “For those of us who were religious or spiritual, it was a very important part of our morale, optimism and overall, it was a part of our survival.”

After returning home, one of Shuman’s assignments was running the Naval Academy’s sailing program.

CDR James L. Griffin ’55, USN

Captured: 19 May 1967

Griffin joined RVAH-13 in 1964, serving in Vietnam on two cruises (1965–1967).

In April 1967, Griffin had completed 100 combat missions. His plane was shot down over Hanoi on 19 May 1967. He would die on 21 May 1967 from injuries sustained in the shoot-down.

He was carried in a “missing in action” status until January 1973, when his death was revealed by the North Vietnamese. On 16 January 1974, the Secretary of the Navy verified Griffin died while a prisoner of war.

Commander Griffin’s awards include the Distinguished Flying Cross with gold star, the Naval Commendation Medal with gold star and combat distinguishing device, the Purple Heart, Republic of Vietnam Meritorious Unit Citation (Gallantry Cross Medal Color with Palm), Vietnam Service Medal with three bronze stars and the Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal.

CAPT John H. Fellowes ’56, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 27 August 1966

Released: 4 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1415 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1708.

Fellowes was serving with VA-65 off the aircraft carrier Constellation when his A-6 Intruder was hit by antiaircraft fire on 27 August 1966. He ejected and was captured, suffering from fractured bones in his back.

Fellowes spent time at five POW prisons. On 10 September 1966, he endured a 12-hour torture session in which he “resisted my captors’ attempts to force a statement condemning my country, I lost the use of both arms for the next four months,” he wrote in a 1976 edition of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine.

Following his return to the United States, he was assigned as an instructor at the Naval Academy. He served at the Academy for four years and then attended the National War College from 1977 to 1978. Fellowes retired from the Navy on 10 July 1986.

In retirement, he mentored midshipmen at the Academy and was a volunteer at home Navy football games.

CAPT John D. Burns ’57, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 4 October 1966

Released: 4 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1415 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1708.

Burns was shot down during a night reconnaissance mission searching for enemy trucks on 4 October 1966 by antiaircraft fire, according to a 3 June 2013 story on gazette.com. During the ejection from his plane, Burns broke three vertebrae.

He spent the first weeks of his captivity strapped to a concrete pallet and then months at a time in solitary confinement, the gazette.com story said. Among the awards Burns earned were the Silver Star, Legion of Merit with Valor, Bronze Star with Combat “V,” two Purple Hearts and the Prisoner of War Medal.

CAPT Leo G. Hyatt ’57, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 13 August 1967

Released: 14 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1430 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1715.

Hyatt learned from a doctor following his imprisonment by the North Vietnamese he had a fractured neck vertebra, “similar to what would happen if someone was hung,” he told yourobserver.com for a 2021 story.

He said he was injured while being tortured. He couldn’t move afterward and couldn’t feed himself for at least five days. Another prisoner fed him and gave him water, saving his life.

Hyatt was on a reconnaissance mission in North Vietnam on 13 August 1967 when his RA-5C Vigilante was hit by antiaircraft fire. A bone in his left shoulder shattered during his ejection from the plane and he was shot in the right arm while trying to evade the North Vietnamese.

Hyatt retired from the Navy in 1986. He earned several awards including a Silver Star, the Legion of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross and two Bronze Stars.

CDR Richard D. Hartman ’57, USN

Captured: 18 July 1967

Hartman was flying an A-4 Skyhawk when it was shot down on 18 July 1967 while on a combat mission over North Vietnam. He was reportedly in radio contact with other pilots who were able to drop supplies to him while he attempted to elude capture.

His captors reported that he died in captivity four days later on 22 July 1967. Hartman’s cause of death was not specified.

One of the rescue helicopters attempting to recover Hartman on 19 July was hit by enemy fire. It crashed and all onboard perished. His remains were repatriated on 6 March 1974.

CAPT John S. McCain III ’58, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 26 October 1967

Released: 14 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1455 and

arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1715.

McCain was flying over Hanoi when his A-4 Skyhawk was hit by antiaircraft fire on 26 October 1967. He ejected, and his right leg, right arm and left arm were broken. The North Vietnamese captured him after pulling him from a lake.

Because his father, John S. McCain Jr. ’31, USN (Ret.), was an admiral at the time of his capture, the North Vietnamese attempted to leverage Commander McCain for propaganda purposes. They filmed an operation to repair his injured leg. He was hospitalized for six weeks before being moved to the “Plantation” POW camp.

McCain spent more than two years in solitary confinement. He rejected any suggestion of preferential treatment from his captors, including an offer to return home where he could receive competent medical care. He said in an account printed in the 14 May 1973 edition of U.S. News and World Report that the final offer to go home coincided with the date his father became commander-in-chief, Pacific Command. He refused to leave before the POWs who preceded him.

During his imprisonment, McCain was bound with ropes, his left arm was rebroken and his ribs were cracked during torture sessions.

McCain was selected as a Distinguished Graduate Award recipient in 2018.

CDR Dennis A. Moore ’60, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 27 October 1965

Released: 12 February 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1405 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1655.

Moore was deployed aboard Bon Homme Richard on 27 October 1965 when he was shot down and forced to eject over North Vietnam. He recounted the ways POWs passed time during an interview published by Montana Public Radio in December 2018. He said once he had cellmates, they would have 30-minute mosquito killing competitions each day.

They would pass along knowledge to each other. For example, he took Spanish in high school and at the Naval Academy.

He would give out five words of vocabulary each day and review with his fellow POWs.

Upon returning to the United States, Moore served as maintenance officer with VF-51 at NAS Miramar and deployed aboard the aircraft carrier Coral Sea (November 1974–July 1975). He participated in operations during the Fall of Saigon in April 1975. He also served as executive officer of VF-191 at NAS Miramar (March–December 1976) and served as commanding officer of VF-191 at NAS Miramar and deployed aboard the aircraft carrier Coral Sea (December 1976–March 1978).

He retired from the Navy on 1 July 1980.

LCDR James J. Connell ’61, USN

Captured: 15 July 1966

Connell was physically abused regularly and kept in solitary confinement for several years by his captors. He died on 14 January 1971 due to his treatment by the North Vietnamese. His fellow POWs were inspired by Connell’s resolve and his Navy Cross citation is a testament to his bravery.

“Under constant pressure from the North Vietnamese in their attempt to gain military information and propaganda material, Lieutenant Commander Connell experienced severe torture with ropes and was kept in almost continuous solitary confinement. As they persisted in their hostile treatment of him, he continued to resist by feigning facial muscle spasms, incoherency of speech and crippled arms with loss of feeling in his fingers.

“The Vietnamese, convinced of his plight, applied shock treatments in an attempt to improve his condition. However, he chose not to indicate improvement for fear of further cruelty. Isolated in a corner of the camp near a work area visited daily by other prisoners, he established and maintained covert communications with changing groups of POWs, thereby serving as a main point of exchange of intelligence information.”

On 15 July 1966, Connell’s plane was shot down. He sustained minor injuries after ejecting but was captured shortly thereafter. His remains were repatriated on 6 March 1974. Among the other awards he earned were the Legion of Merit and Distinguished Flying Cross.

CDR Charles D. Stackhouse ’61, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 25 April 1967

Released: 4 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1425 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1730.

Stackhouse was flying an A-4 Skyhawk when enemy fire struck his plane during a bombing mission over North Vietnam on 25 April 1967.

His Silver Star citation credits Stackhouse for saving the life of his wingman. “With both planes under attack by enemy fighters, he maneuvered his aircraft in support of his wingman, calling defensive turns which enabled the wingman to repeatedly evade his attackers. While so doing, Lieutenant Commander Stackhouse was shot down by his attacker. His courage and devotion to duty under conditions of gravest personal danger contributed substantially to the success of the mission. By his heroic disregard for his own safety, Lieutenant Commander Stackhouse was directly responsible for saving the life of his wingman, thereby upholding the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service,” the citation reads.

He spent 2,141 days as a POW. He earned a Distinguished Service Medal, two Purple Hearts and Legion of Merit and the Bronze Star both with “V” designation. He retired from the Navy after 21 years on 1 February 1982.

CAPT Edward A. Davis ’62, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 26 August 1965

Released: 12 February 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1405 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1655.

Davis was shot down on his 57th combat mission over North Vietnam while flying an A-1H Skyraider on 26 August 1965.

He was captured after a night spent in a rainy ditch then marched 19 days to Hanoi. Among the torture techniques used on him by his captors, Davis endured the “rope trick” in which his arms were bound and forced behind his back and toward his head.

Davis smuggled out a puppy named Maco from his North Vietnamese prison on his flight to Clark Air Base in the Philippines. After returning home, he served as executive officer of the Navy ROTC unit at the University of Virginia (August 1975–June 1978). His final assignment was as commander of the Navy Recruiting District at Harrisburg, PA. He retired from the Navy on 29 March 1987.

Among Davis’ honors were three Silver Stars, the Legion of Merit with combat citation, four Bronze Stars, five Air Medals and two Purple Hearts.

CAPT Michael P. Cronin ’63, USNR (Ret.)

Captured: 13 January 1967

Released: 4 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1425 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1730.

Cronin was flying an A-4 Skyhawk when he was shot down on 13 January 1967. He was captured and proceeded on a 16-day march to Hanoi. He estimated he was tortured using the “rope trick” between 20 and 30 times.

After returning to the United States, Cronin served as an instructor pilot with VF-126 at NAS Miramar, CA (August 1973– January 1976). He also was a C-9 Skytrain II pilot with VR-30 at NAS Alameda, CA, from January 1976 until he entered the U.S. Naval Reserve on 1 July 1976. He then served as a reserve C-9 pilot (1976 to 1980). He remained in the Naval Reserve in a non-flying status until his retirement on 1 August 1992.

Among his honors, Cronin was awarded two Silver Stars, the Legion of Merit with Combat “V,” the Distinguished Flying Cross, four Bronze Stars with Combat “V,” two Purple Hearts and three Navy Commendation Medals with Combat “V.”

CAPT Wilson D. Key ’63, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 17 November 1967

Released: 14 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1455 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1715.

Key was shot down and captured about 20 miles east of Hanoi on 17 November 1967. A 31 August 2018 journalpatriot.com story shared Key’s actions as his captors were taking him to Hanoi. He untied his hands and attempted to escape.

“I jumped out the back of the truck,” he wrote in a 1997 letter, according to journalpatriot.com. “Unfortunately, I jumped in the middle of a village (the timing wasn’t my choice; one of the guards discovered that I was untied.) Nevertheless, I managed to make my way through the village toward the south and suddenly the Red River lay before me (they were chasing me by this time).

I jumped in and was able to swim under water far enough so that they lost me. I evaded for about an hour, I guess, before the armada of boats they launched found me. The only repercussions for the escape was a few belts from the guards in the truck and a much more comprehensive tie job for the rest of the trip to Hanoi.”

After his return to the United States, Key served at the Naval Academy twice. The first was as a physics instructor (June 1977– 1979) then as director of math and science and commodore of the sailing squadron (June 1990 until his retirement from the Navy on 1 July 1993).

CDR Aubrey A. Nichols ’64, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 19 May 1972

Released: 28 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1530 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1824.

Nichols’ A-7 Corsair II was shot down over North Vietnam on 19 May 1972. He spent two months in solitary confinement before joining his fellow POWs. The inhumane torture at the Hanoi Hilton had largely ceased by the time Nichols arrived but he was still pressed to divulge information and to write anti-war propaganda which he refused to do, according to a 28 September 2016 story posted at Kirtland.af.mil.

After returning to the United States, Nichols served as an A-7 pilot for five years. His final assignment was with the Defense Nuclear Agency Field Command at Kirtland AFB, NM, from January 1985 until his retirement from the Navy on 1 June 1988.

VADM Joseph S. Mobley ’66, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 24 June 1968

Released: 14 March 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1515 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1811.

Mobley’s A-6 Intruder was hit by antiaircraft fire on 24 June 1968. His leg was broken when he was shot down.

His captors tied him, standing, to a pillar and he was beaten and interrogated in front of a crowd. He was denied immediate medical help and set his broken leg himself once he was placed in a prison cell.

When he retired on 1 June 2001, he was the last Vietnam POW on active duty. Among Mobley’s assignments after returning home were commanding officer of Kalamazoo and Saratoga.

He directed his aircraft carrier’s operations in Operation Desert Storm. After the Persian Gulf War, Admiral Mobley served as Chief of Staff of U.S. Sixth Fleet from May 1991 to August 1992.

Mobley also served as commander of Carrier Group TWO and commander of the Naval Safety Center (September 1994– October 1995). He was director of the Navy Staff in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (November 1995–September 1996), and was director for Operations of U.S. Pacific Command (September 1996–November 1998). His final command was as commander of the Naval Air Force of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet.

LCDR Frederick J. Masterson ’67, USN (Ret.)

Captured: 11 July 1972

Released: 29 February 1973, at Gia Lam Airport, Hanoi, North Vietnam, at 1600 and arriving at Clark Air Base, Philippines, at 1832.

Masterson served as an F-4 RIO with VF-103 at NAS Oceana from May 1970 to May 1972. Masterson was deployed aboard the aircraft carrier Saratoga from May 1972 until he was forced to eject over North Vietnam on 11 July 1972. He suffered a partially paralyzed right hand when he broke his arm as he was ejecting from his plane.

Following his return to the United States, Masterson served with the F-4 Replacement Air Group VF-101 at NAS Oceana from June 1974 until he was medically retired from the Navy on

1 March 1977. Masterson received a Bronze Star with Valor.

Editor’s Note: Information from veteranstributes.org, pownetwork. org, usnamemorialhall.org, arlingtoncemetery.net and Captain John McGrath ’62, USN (Ret.), contributed to this report.

___________________________

IN MEMORIAM

The Naval Academy honors alumni Killed in Action and those who were operational losses during the Vietnam War in Memorial Hall. Shipmate honors their sacrifice and recommends learning more about them at VMH: Vietnam (usnamemorialhall.org).

Class of 1943

LtCol George E. Chamberlin Jr., USMC #

Class of 1945

LCDR Roger H. Mullins, USN *

Class of 1947

CDR James D. Lahaye, USN

CDR Valentin G. Matula, USN *

Class of 1948

CAPT Hubert B. Loheed, USN

Col Robert N. Smith, USMC

CAPT Roger M. Netherland, USN

Class of 1949

CDR Clarence W. Stoddard Jr., USN

CDR Edgar A. Rawsthrone, USN

CAPT Homer L. Smith, USN

CDR Leonard F. Vogt Jr., USN

Class of 1950

CDR Robert C. Frosio, USN *

Lt Col Christopher Braybrooke, USAF *

Class of 1951

Col Donald. E. Westbrook, USAF

CAPT Peter W. Sherman, USN

Col Richard A. Walsh III, USAF

CDR Clyde R. Welch, USN *

Class of 1952

Lt Col Charles D. Ballou, USAF

Col Charles Harold W. Read Jr., USAF

CAPT Donald D. Aldern, USN

CAPT John C. Ellison, USN

Col John F. O’Grady, USAF

Capt Thomas C. McEwen Jr., USAF #

Maj Robert. G. Bell, USAF *

Maj Joseph E. Bower, USAF

Maj Raymond L. Tacke, USAF *

Class of 1953

Col George E. Tyler, USAF

LCDR Harvey Chadwick K. Aiau, USN

Capt John H. McClean, USAF

Col Oscar M. Dardeau Jr., USAF

CDR Peter H. Krusi, USN

LtCol William G. Leftwich Jr., USMC

LCDR Donald W. “Dan” Beard, USN *

Maj Robert J. Cameron, USAF *

LtCol Lee Snead, USMC *

CAPT Edmund B. Taylor Jr., USN *

Class of 1954

Col Charles S. Rowley, USAF

CAPT Ernest A. Stamm, USN

LCDR Kenneth E. Hume, USN

LCDR Charles D. Schoonover, USN *

Class of 1955

Lt Col Donald L. Rissi, USAF

Maj Jay Coates Jr., USAF

Lt Col Henry M. Serex, USAF

CDR James L. Griffin, USN

Maj John L. McElroy, USAF #

Maj Thomas D. Moore Jr., USAF *

Class of 1956

Col Charles A. Levis, USAF

Col Ernest A. Olds, USAF

CDR George H. Wilkins, USN

Maj Philippe B. Fales, USAF

LCDR Wilmer P. Cook, USN

Class of 1957

Capt Charles F. Swope, USAF

Maj David I. Wright, USAF

Maj Gardner Brewer, USAF

Lt Col Herbert Doby, USAF

Maj Howard V. Andre Jr., USAF

CDR John D. Peace III, USN

LCDR John E. Bartocci, USN

CDR Richard D. Hartman, USN

Lt Col Robert M. Brown, USAF

LCDR Donald G. Brown, USN *

Capt Kurt W. Gareiss, USAF *

Class of 1958

LCDR Carl J. Peterson, USN

Capt Edward R. Browne, USMC

Lt Col John W. Held, USAF

Capt Wesley R. Phengar, USMC *

Class of 1959

LT Charles D. Witt, USN

Lt Col Glenn R. Morrison Jr., USAF

Maj Jack W. Phillips, USMC

Capt Roland R. Obenland, USAF

LT William L. Brown, USN

Col Winfield W. Sisson, USMC *

LT Gary D. Hopps, USN #

Maj Wayne R. Hyatt, USMC

LCDR Lawrence Gosen, USN

Class of 1960

Maj Donnie L. Darrow, USMC

Capt Martin N. Tull, USMC

LT William M. Roark, USN

LT Malcolm A. Avore, USN *

Capt Alexander McIver, USAF #

CPT Don T. Elledge, USA #

1st Lt Donald A. Mollicone, USAF *

Class of 1961

LT Gene R. Gollahon, USN

Capt Henry Kolakowski Jr., USMC

LCDR James J. Connell, USN

LT John D. Prudhomme, USN

Capt John L. Prichard, USMC

LCDR Robert S. Graustein, USN

Capt Sterling K. Coates, USMC

LTJG Terence M. Murphy, USN

Capt Willard D. Marshall, USMC

LT Frank M. Brown, USN *

Class of 1962

Capt Barry R. Delphin, USAF

Maj Bradley G. Cuthbert, USAF

LT Charles A. Knochel, USN

LCDR Charles R. Lee, USN

LT Charles W. Fryer, USN

CDR Clarence O. Tolbert, USN

1st Lt Cyrus S. Roberts IV, USAF

Capt John A. Lavoo, USMC

Maj Lucius L. Heiskell, USAF

Lt Michael T. Newell, USMC

LT Richard L. Laws, USN

Capt Thomas L. Carter, USMC

LTJG Thomas E. Murray, USN *

LTJG Geoffrey H. Osborn, USN *

LT Jack D. Renfro, USN *

LT Richard W. Hastings, USN *

LCDR John R. Poe, USN *

Class of 1963

LCDR Alexander J. Palenscar III, USN

LTJG Carl L. Doughtie, USN

LCDR Charles W. Marik, USN

LT Daniel H. Moran Jr., USN

LTJG Donald C. Maclaughlin Jr., USN

LCDR Erwin B. Templin Jr., USN

LT Frederick E. Trani, USN

LCDR James K. Patterson, USN

LTJG Jerald L. Pinneker, USN

LCDR John B. Worcester, USN

LCDR Kenneth R. Buell, USN

LT Stanley K. Smiley, USN

LT William C. Fitzgerald, USN

Richard A. Schenk #

Class of 1964

LT Barry W. Hooper, USN

LCDR Charles C. Parish, USN

LCDR Geoffrey R. Shumway IV, USN

LCDR Jerry F. Hogan, USN

LT Michael R. Collins, USN

LTJG Robin B. Cassell, USN

1stLt Thomas J. Holden, USMC

LCDR Virgil K. Cameron, USN

Capt William A. Griffis III, USMC

LTJG Gerald W. Siebe, USN *

Class of 1965

LCDR Edward J. Broms Jr., USN

1stLt Richard W. Piatt, USMC

2ndLt Ronald W. Meyer, USMC

LT William L. Covington, USN

1stLt William M. Grammar, USMC

LT Lynn M. Travis, USN

LTJG Warren W. Boles, USN

LT John C. Lindahl, USN

LT Gary B. Simkins, USN

Class of 1966

LT Bruce C. Fryar, USN

2ndLt Charles W. F. Warner, USMC

LT Donald G. Droz, USN

LTJG Douglas D. Vaughn, USN

Capt John W. Consolvo Jr., USMC

2ndLt John W. Doherty, USMC

2ndLt Larry V. Chmiel, USMC

LT Leland C. Cooke Sage, USN

LCDR Marvin B. Christopher Wiles, USN

Capt Michael C. Wunsch, USMC

LCDR Nicholas G. Brooks, USN

LCDR Orland J. Pender Jr., USN

1stLt Raymond C. Daley, USMC

CAPT Robert D. Huie Jr., USMC

LT Victor P. Buckley, USN

LTJG William T. Morris III, USN

Class of 1967

2ndLt Alan A. Kettner, USMC

LCDR Barton S. Creed, USN

LTJG Hal C. Castle Jr., USN

2ndLt Henry A. Wright, USMC

LTJG Kenneth D. Norton, USN

LT Richard C. Deuter, USN

2ndLt Robert E. Tuttle, USMC

2ndLt Thomas J. Weiss, USMC

1stLt Gary E. Holtzclaw, USMC *

Class of 1968

LT David M. Thompson, USN

1stLt James D. Jones, USMC

LCDR Philip S. Clark Jr., USN

LTJG Richard H. Buzzell, USN

2ndLt Theodore R. Vivilacqua, USMC

LT Melvin S. Dry, USN

Class of 1969

Capt Scott D. Ketchie, USMC

LTJG Arnold W. Barden Jr., USN

PFC David D. Peppin Jr., USMC #

Key

Naval Academy graduates KIA in Vietnam

# Nongraduates KIA in Vietnam

* Alumni who were operational losses